The Sketchbook

Why I Started My Father’s Daughter

A collection of idioms

I’ve heard a lot about the man my Father once was. In fact, most of my own identity is comprised of idioms alluding to genetic similarities recited to me by family members and their well-intentioned friends. “You could draw before you could talk…or walk!” “You are the spitting image of your Dad.” “You are your Father’s Daughter.”

Identity is a slippery and malleable thing. Most people do not forge their own sense of self. They inherit it from their parents values and interests. They internalize it, live in it, almost without question. At times, I feel very lucky. My Mom and Dad never forced a path on me. They encouraged my interests, strange as they were (thank you parents for not locking me away when I tried to become at age 12–I kid you not–a witch), and wanted more than anything for me to forge my own path. However, the older I get, the more I look to them as guides for who I am meant to be.

My Dad died in a hospice seven years ago, two days after Valentine’s Day, surrounded by family members I hadn’t seen or spoken to in years. I was a sophomore in college, located 410 miles away. Upon my arrival, I remember somewhat pathetically presenting him with a Valentine’s Day card I had drawn, narrating over the sounds of beeping ventilators that I had painted him a rose – something he had taught me how to do when I was in middle school. I knew he couldn’t hear me. Even if he did, he had forgotten my name months earlier. The faint recognition registered in his eyes when I visited his nursing home over my Thanksgiving break most likely was triggered by his memories of one of my much older half-sisters, who I resemble. Like her, I inherited Dad’s sharp cheekbones and dark brown eyes.

“Most of my identity is comprised of idioms alluding to genetic similarities recited to me by family members and their well-intentioned friends. “You could draw before you could talk!” “You are your Father’s Daughter.”

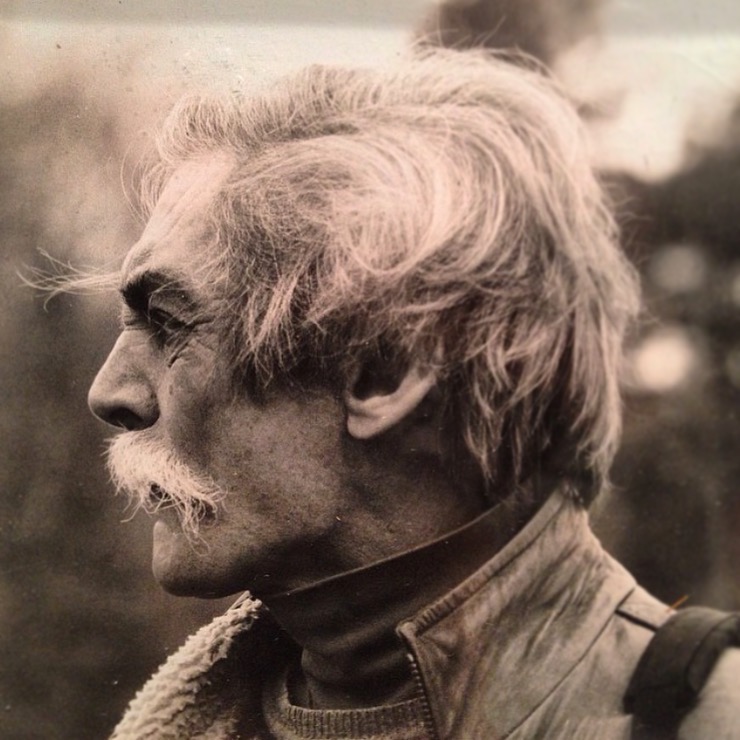

My father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease when I was in Middle School. My parents had an significant age difference that I didn’t know was unusual until a classmate pointed out the disparity. He had retired from his career as a successful graphic and exhibition designer years before. Instead it was my mother, an academic and museum curator, who took over as the head of our family. She signed my math tests when I did poorly (a competency I did not inherit from my father alas); was the gatekeeper of all sleepover and taxiing logistics in our suburban town; and as I got older, the biographer of Dad’s past. She tried to bring back to life memories of him as a vigorous, engaged and charming man before he faded into an object on a couch, watching Turner Classic Movies for 9 hours a day.

I cherish my memories of him before he slipped into the curse of total confusion, then darkness. The “long goodbye” is what many people call it. There were years where I had the opportunity to learn about him, from him; ask questions, listen to stories. I can’t say I utilized that window of opportunity effectively, but then again, I was just a kid and the product of his third marriage: the sixth daughter, seventh child, of man with a complicated past.

He never talked about his parents. I learned that he was left with his sister at an orphanage in Carteret, New Jersey, at a young age where the nuns had forbid him from writing with his left hand, smacking him repeatedly until he learned how to use his right. I learned that when he started drawing, he was chastised and labeled a sissy. He became a foster child in his teens. Most days during my adolescence, I considered my dad more grandfather than parent. I loved him, but was often annoyed by my pinch-hitting responsibilities as his caretaker.

Looking back, I can see that my well-intentioned Alzheimer’s advocacy efforts in High School allowed me to hide behind the disease; to protect myself from the hard work of learning to love someone for who they were, only to lose them anyway. I criticized my half-siblings for distancing themselves from him (another form of self-defense) but while I was writing detailed biology papers on the devastating stages of the disease and organizing fundraisers for the Alzheimer’s Association, I was inadvertently building a wall to hide behind.

What we shared instead of Take Your Daughter to Work Day, teaching me how to drive, or terrorizing my high school boyfriends, was art. I have vague memories of Dad carrying a black, leather-bound sketchbook wherever we went–sketchbooks that I would pour over in college as I desperately searched for a part of him to hold on to. There was no doubt that I inherited my artistic abilities from him, as did one of my older half-sisters. There was a comforting familiarity in our respective styles of drawing, painting and even penmanship that made me feel connected to him and to his forerunners -relatives I never knew. For awhile I had even thought I might go to art school. Around the time my dad lost the ability to walk independently, I was spending six weeks at Rhode Island School of Design’s summer art program. But like most teenagers, my interests were fleeting and I quickly decided I’d rather go to a college with fraternity parties and well-rounded academic programs where I could feel like a regular eighteen-year-old, who hadn’t changed her father’s diaper or spent weekend nights supervising an 80 year old man.

There was no doubt that I inherited my artistic abilities from him, as did one of my older half-sisters. There was a comforting familiarity in our respective styles of drawing, painting and even penmanship that made me feel connected to him and to his forerunners -relatives I never knew.

Having a loved one with Alzheimer’s is hard, but in more ways than advertised. Yes, this degenerative disease robbed my father of his memories, his body, his life, and the retirement he deserved. But it also robbed me of my understanding of parts of who I was, and now, who I am. The day he was diagnosed I hadn’t known that the clock was ticking. I was a kid, and grown-ups, especially the elderly, weren’t ‘fun.’ Parents often encourage their kids to get to know their grandparents before they are gone. As a child you don’t understand that your family–the good parts and the bad–are part of who you are. My own understanding of (and respect for) my mom grows every day. When I find myself explaining the plot of a book from start to finish, spoiling the whole story (something she always does), or writing little hints on Christmas presents for my boyfriend (something I picked up from my grandmother), I feel this undeniable comfort in knowing where these quirks came from.

At 27, I think a lot about where I am going and who I’d like to be. I often feel restless because I don’t have the answer–like I’m about to finish a 600 piece jigsaw puzzle, but a couple of pieces – or maybe an entire critical section — have gone missing. I’ve made at least two significant career pivots, and am not sure what direction I’d like to next pursue. I spend a lot of time refusing to grow up, because I don’t know who that person should be. My complicated grief over the loss of my father has shifted in the seven years since he died; now more than ever I mourn the ghost of his identity, which is so hard to fix. His likes and his dislikes. His allergies, his hobbies, his pet peeves; the formative moments of his life before I came along. Looking down the barrel of my twenties, I wonder if I will ever truly understand who I am, or if the part of me that feels empty will one day feel whole. But I do know that every time I pick up a pen and draw, I feel a sense of peace. So I will continue to illustrate moments of beauty and memorialize happy vignettes in ink and paint, so those memories quite literally never fade. Just as my Dad taught me to do.

I do know that every time I pick up a pen and draw, I feel a sense of peace. So I will continue to illustrate moments of beauty and memorialize happy vignettes in ink and paint, so those memories quite literally never fade. Just as my Dad taught me to do.

To support Alzheimer’s Disease research, click here. To learn more about how to help a loved one with Alzheimer’s, click here.

[…] much I loved it, that summer was the last time I enrolled in a “serious” art program (thats a different story…). Since I started My Father’s Daughter Designs in 2019, I have fantasized about going […]